‘Lost’ and Found

In May 1943, the Japanese began to construct an airfield to the east of the Changi Camp area. Accommodation was required for Japanese airfield engineers and support troops, so the Japanese began to move prisoners out of Changi. The first POW to be affected were those in Kitchener Barracks. They were moved to Selarang Barracks. Roberts Barracks remained as the POW hospital. From the hospital, Stanley could see, in the distance, parties of prisoners working clearing the vegetation and levelling the land for the airstrip.

By early 1944, there were still some 8,500 POWs in the Changi Camp area, of these around 1,500 were ill with malaria, dysentery and severe malnutrition.

In May 1944, Roberts and Selarang Barracks were taken over by the Japanese as well. All the POW, with the exception of 1,200 classified as sick by the Japanese were moved to Changi Prison. At this time there were some 12,000 POW at Changi and Selarang. Of these some 5,000 managed to cram into the prison itself, The remainder lived in attap huts they built themselves outside the prison walls. At the same time, survivors of the Thailand/Burma railroad were brought to Changi along with Dutch, American, and surprisingly some Italian Prisoners. The Italians were the crew of a submarine which, was at Singapore at the time of the Italian surrender to the Allies. On declining the Japanese invitation to continue the war with them, the Italians were incarcerated with their erstwhile enemies. The Changi cantonment was now devoid of POW. The surviving civilians at the prison were moved to Sime Road internment camp in Singapore Town where they continued to suffer and die.

Block 151 now became became a store, ending the brief life of Saint Luke’s Chapel. The mural of St Luke in Prison was almost completely destroyed when the lower portion of the wall it was painted on was demolished to make a link to the adjoining room. The walls of the chapel were then distempered over, hiding the murals from view. The mural of the Crucifixion was also damaged when a doorway was made into the adjoining room.

In September 1945, following the Japanese surrender, the Royal Engineers returned to Changi. The Japanese, now prisoners themselves, were used to help clear up the detritus of war at Changi, and to work on improving the airfield. Their conditions of work were humane, unlike the treatment they meted out to their prisoners. The army soon realised that there would not be any benefit in reconstructing the gun batteries, but the airfield had real possibilities. They leased the airfield to the Royal Air Force in 1946. The Air Force had been finding that Kallang was too small for the use it was being put to, and gratefully took over the Changi Camp area, and the airfield development work.

In Block 151, the former St. Luke’s Chapel was yet again used as a store room, this time by the RAF. Later, as the new RAF Station Changi became more organised and continued to grow, Block 151 became accommodation for Airmen. The Chapel now became a barrack room, just as it had been before the war. Stanley Warren’s murals still lay under their covering of distemper.

REDISCOVERY

Perhaps surprisingly, here are two official stories concerning the ‘rediscovery’ of the murals, both dating from 1958. The first story concerns an unnamed RAF National Serviceman. He was ordered to clean up the storeroom which had served as the POW Chapel. On starting work, he discovered that some paintings lay under the distemper covering the walls. He reported this to an officer, who, on examining the paintings, realised the importance of the discovery. The second story is that the murals were discovered by three members of the Singapore Armed Forces working in the storeroom. Once rediscovered, the distemper covering the murals was carefully removed and four complete, and the top quarter of a fifth mural were revealed. There was no signature on any of the murals, so the identity of the artist was a mystery. An initial search was instigated, but failed. An all out search was then started. In 1958, a Far East Air Force publication, ‘Tale Spin’ printed pictures of two of the murals, stated that they had been painted by an unknown POW during the Japanese Occupation.

NOT REALLY LOST

The two official stories of the rediscovery of the murals are similar enough to be variations of the same tale, but they are both inaccurate. The murals may have been ‘officially rediscovered’ in 1958, but they most certainly had not been lost. They were were visible long before 1958, people knew about them, and visited them.

In 1949, RAF Serviceman Neville Stubbings was stationed in Changi He remember ‘old sweats’ taking a great pleasure in telling young servicemen like him that the pictures on the walls had been painted with prisoner’s blood.

Between 1951 and 1952, Brian Northover was living in Block 151 and was sleeping in the former Saint Luke’s Chapel. The murals were visible and he made some enquiries as to their origin, learning a little of their history. Brian believes that the murals were distempered over again after he left Changi, but before their ‘official rediscovery’.

Joe Duncan, seen right outside Block 151, was in Changi from February 1953 to July 54 and billeted in Block 151. He has no recollection of more than three murals being visible; The Ascension, The Crucifixion and The Last Supper. indeed, he only has photos of these three. He also remembers a story that newcomers to the Block were told that the murals had been painted by Prisoners of War during the Japanese occupation.

Joe Duncan, seen right outside Block 151, was in Changi from February 1953 to July 54 and billeted in Block 151. He has no recollection of more than three murals being visible; The Ascension, The Crucifixion and The Last Supper. indeed, he only has photos of these three. He also remembers a story that newcomers to the Block were told that the murals had been painted by Prisoners of War during the Japanese occupation.

William Fowler lived in Block 151 between July 1953 and June 1955. He remembered the murals being exposed with one of them damaged.

Tony Lowe was billeted in Block 151 from April 1956 to February 1958. He remembers that on his arrival at Block 151, the murals were visible. He can also remember visitors being shown the murals when he was there.

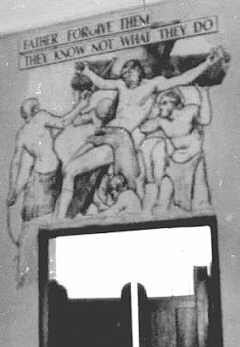

Peter Sanders was in the Royal Air Force at Changi between 1961 to 1964. From 1961 until late 1962 he lived in Block 151 in the room that was St Luke’s Chapel. His bed was opposite the mural of the Crucifixion. He found that the words above the mural, “Father forgive them for they know not what they do”, to be, “a sobering thought on waking up in the morning after a night out Singapore”".

Peter Sanders was in the Royal Air Force at Changi between 1961 to 1964. From 1961 until late 1962 he lived in Block 151 in the room that was St Luke’s Chapel. His bed was opposite the mural of the Crucifixion. He found that the words above the mural, “Father forgive them for they know not what they do”, to be, “a sobering thought on waking up in the morning after a night out Singapore”".

Not long after he and his comrades were moved out of the room, it was converted back into a Chapel. Peter thinks that this was probably in early 1963. Later that year, he went back to the Chapel to watch Stanley Warren carrying out his first restoration work. Stanley told him that he had been very reluctant to return to Singapore, and that he was not sure if he would complete the restoration of all the murals as they brought back too many bad memories for him.

The murals of the Ascension, Crucifixion and Last Supper before restoration. The damage to the Crucifixion where a doorway was made in the wall can easily be seen. The photographs are shown by courtesy of Peter Sanders.

Ronald Davidson first saw the Changi Murals in 1956 when he was on detachment to Changi from Kuala Lumpur. His photograph of the Mural of the Crucifixion (left), clearly shows the door cut into the wall, which destroyed the lower potion of the Mural.

Ronald Davidson first saw the Changi Murals in 1956 when he was on detachment to Changi from Kuala Lumpur. His photograph of the Mural of the Crucifixion (left), clearly shows the door cut into the wall, which destroyed the lower potion of the Mural.

It is possible that the existence of the murals was not have been widely known throughout RAF Changi . As the room in which the murals were was being used for accommodation purposes, their importance had certainly not been realised. Word of their existence may not have been widely spread. Perhaps the ‘official discovery’ took place after the significance and historical value of the murals had been realised.

Albert Peters spent two and a half years with the RAF at Changi from January 1953 to June 1956. He was initially billeted in Block 151 before moving to another block. Albert, a practicing Christian, joined the Changi Branch of SASRA (Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Scripture Readers Association), eventually becoming Branch Secretary. He knew all of the Chaplains at Changi, including the Principal Chaplain FEAF (Far East Air Force). Albert says that if, “something of such a deeply religious nature and as significant as the Changi Murals, had been discovered during my two and a half years at Changi, I find it difficult to understand how my Christian friends and I didn’t come to know about them. I would have thought that all three station chaplains and those at FEAF HQ would have known, and that news would have spread to those of us who were active in Christian work on the Station and others who were regular attendees at the three churches. It just seems odd to me that if the murals were discovered before 1956 and people were coming to see them, that I was so oblivious to their existence”. Perhaps, but God works in strange and mysterious ways.

The photo on the right is from Graham Langford, who was stationed at RAF Changi as a Corporal Air Radar Fitter from 16th August 1969 until late December 1971.He lived in Block 151. He heard about the Murals being in the barrack block from other Airmen. The whole of Block 151 was being used for Airmen accommodation. The room with the murals was empty and unlocked and was not considered of any significance that he was aware of. There was no furniture in it and it certainly wasn’t used as a chapel. He had heard that the murals had been ‘painted’ by some prisoners-of-war using mud and blood.

The photo on the right is from Graham Langford, who was stationed at RAF Changi as a Corporal Air Radar Fitter from 16th August 1969 until late December 1971.He lived in Block 151. He heard about the Murals being in the barrack block from other Airmen. The whole of Block 151 was being used for Airmen accommodation. The room with the murals was empty and unlocked and was not considered of any significance that he was aware of. There was no furniture in it and it certainly wasn’t used as a chapel. He had heard that the murals had been ‘painted’ by some prisoners-of-war using mud and blood.

THE SEARCH FOR THE ARTIST

Ronald Searle, a well known artist and cartoonist, was suggested as being the artist. He had been a POW, and had painted some murals twelve feet in height, in Changi Prison. He however, said that he had not painted the Roberts Barracks murals. Efforts to find the artist continued. A letter from a young lady in Singapore was printed in the Daily Mirror, a popular British newspaper, along with one of the ‘Tale Spin’ pictures. A large response brought many theories, but still no artist. The Singapore Sunday Times had also been searching, but without success.

Eventually, the mystery artist’s name accidentally came to light in Singapore, in the Far East Air Force Education Library. A reader found a book entitled “Churches of Captivity in Malaya”, containing articles about small churches and chapels made by POWs.

One article concerned the Chapel of St. Luke the Physician in Block 151 Roberts Barracks. The article, illustrated with a sketch (right) of the chapel, also gave a description of the murals, and at the foot of the sketch was written, “ Drawn by Bdr Stanley Warren, R.A.”. The Daily Mirror was notified of the artist’s name, and published it.

One article concerned the Chapel of St. Luke the Physician in Block 151 Roberts Barracks. The article, illustrated with a sketch (right) of the chapel, also gave a description of the murals, and at the foot of the sketch was written, “ Drawn by Bdr Stanley Warren, R.A.”. The Daily Mirror was notified of the artist’s name, and published it.

In February 1959 Stanley Warren was found living in London with his wife and son. He had not given up art and since 9th September 1957 had been teaching the subject at the Sir William Collins Secondary School where he later became Deputy Head of Brunel House from 1963-1965. He also took art students on two trips to Italy, in particular Florence, in the early 1960s.

Meanwhile The Singapore Sunday Times had made contact Philip Weyer, a bank employee working in Singapore. Philip had been in the prison hospital with Stanley, and told the newspaper that Stanley was a quiet, religious man who had refused to sign his work despite pleas from his comrades. Stanley had insisted that he had painted his pictures as a gift to God.

Years later, Stanley Warren told of how he came to draw this sketch. “One day, a prisoner came to me in camp and said, “Can you draw me a sketch of the chapel?”, and he was so persistent.” The prisoner worked for the church, so Stanley drew a black pencil sketch on grey wrapping paper for him.